| Pop Culture Gadabout | ||

|

Monday, May 26, 2014 ( 5/26/2014 09:43:00 PM ) Bill S.  The two new pieces prove to be the most visually straightforward of the book’s adaptations. Antonella Caputo and Craig Wilson’s version of Wells’ classic time traveling adventure even reminded me of George Pal’s 1960 movie adaptation in its storytelling style in places, though, thankfully scripter Caputo remains truer to the actual plot specifics. Would have liked to have seen more shadowy imagery in David Hontiveros and Rene Maniquis’ remake of Moreau, though this version does capture Welles’ mordant consideration of the thin line between humanity and animalism. The book’s repeat GN adaptation, Rod Lott and Simon Gane’s version of The Invisible Man, proves a little less visually traditional, showcasing Gane’s sardonically cartoonish take on Wells’ s-f horror tale. Perusing it, I couldn’t help recalling James Whale’s 1933 movie version of the story with Whale’s typical blend of the grotesquely comic and horrific. If I keep coming back to movie versions of these works, perhaps it’s because Wells’ novels have arguably sparked more diverse and classic films than any other science-fantasist. It’s a testament to the artists in this book that they’re able to hold their own against already established images that many of us have in our heads. The shorter returning works in the book prove slighter but satisfying: editor Pomplun and Rich Tommaso’s version of “The Inexperienced Ghost” provides a witty take on one of the writer’s more lighthearted works, while Brad Teare’s five-page woodcut version of the apocalyptic “The Star” proves moodily reminiscent of the works of graphic storytelling pioneer Lynd Ward. The set opens with an amusing one-page “Believe It Or Not” parody by Mort Castle and Kevin Atkinson recounting the too-brief meetings between Wells and Orson Welles, who notoriously panicked radio listeners in 1938 thirties with his adaptation of War of the Worlds. This meeting of the minds proved anything but groundbreaking, as the actor/moviemaker used the occasion to primarily plug his upcoming Citizen Kane. Sometimes innovators are only interested in plugging their own works.

(First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Sunday, July 21, 2013 ( 7/21/2013 02:57:00 PM ) Bill S.  The pieces in this collection primarily come from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and largely can be divided into two categories: stories about life in the frontier and fables that had clearly been passed down through the generations. Of the former, one highlight is the collection’s opener, Zitkala-Sa’s “The Soft-Hearted Sioux” (as interpreted by Benjamin Truman, Jim McMunn and Timothy Truman), tells of the internal conflicts faced by a mission school educated Sioux man who returns to his tribe as a Christian missionary. Shunned by his tribe, he winds up being condemned by both worlds, leaving the reader to ponder what historically has been done to young native peoples in the name of “salvation.” Per the majority of the book’s story entries, the McMunn/Truman art aims for a more naturalistic illustrative style, while the fables play with more stylized renderings (e.g., Buffalo Bird Woman’s “The Story of Itsikamahadish and the Wild Potato,” which depicts its coyote formed protagonist in the style of a Warner Bros. Cartoon). There are a lot of Earth tones in this book much so that when more cartoony bright colors show up, it’s almost startling. A good many of the tales focus on the relationship between human protagonists and nature: in Charles Eastman’s “On Wolf Mountain,” (adapted by Joseph Bruchac and Robby McMurtry), a wolf named Manitoo comes up against a tribe of Lakota and a pair of white sheep herders in the midst of a harsh Big Horn Mountains winter; the former respect the creature as fellow natives of the land; the latter see both wolf and native peoples as obstacles to “civilization.” McMurtry’s linework, which at times reminded me of William Mesner-Loebs’ great Journey series, is suited to the tale’s Jack London-esque tone. McMurtry reportedly died from a gunshot just weeks after finishing the art in this piece, and his expressive art has me curious to seek out some of his historical graphic novels. In a work adapted from a more recently published story by associate editor Bruchac, “Two Wolves” encounter each by a late night campfire; the first is an “Indian boy” bounty hunter hired to track the wolf responsible for the deaths of several sheep in the area. The two bond over a meal, though we’re never sure until the end if either will try to kill the other before the night is out. Illustrated by John Findley (best known for the western horror series “Tex Arcana”), the more modern tale fits comfortably within the thematic confines of its 19th and 20th century forebearers. A few pieces strive for more direct social commentary: Handsome Lake’s “How the White Race Came to America” (adapted by editor Pomplun and artist Roy Boney Jr.) is an example of the Senecan religious leader’s curious blending of Native American and Christian religious beliefs, which tells the story of how the devil sent white settlers to America. Royal Roger Eubanks’ “The Middle Man” depicts how the Dawes Act of 1887 paved the way for “a thriving industry of unscrupulous individuals that bought and sold land and mineral rights,” fleecing the Native Americans who originally held the property in the process. More an essay (complete with footnotes) than a story, “Middle Man” does provide a glimpse into the ways that institutionalized racism – one aspect of the Dawes Act stipulated that full-blood Native landholders had more restrictions placed on them than mixed-blood Natives, for instance – aided in the exploitation of indigenous peoples. The fables tend toward the more lighthearted or uplifting. Bertrand M.O. Walker’s “the Prehistoric Race” (adapted by Pomplun and artist Tara Audibert) retells a comic legend of how a turtle outsmarted a group of his fellow creatures in a race across a lake; Buffalo Bird Woman’s coyote story is a broadly comic piece whose punchline revolves around flatulence, while Elias Johnson’s “The Hunter & Medicine Legend” (adapted by Andrea Grant and Toby Cypress) tells of a hunter brought back to life by the animals who consider him their benefactor. There may be more talking animals in the book than there were the last five “Graphic Classics” volumes, but it’s well in keeping with the history of comic books. Another strong and illuminating set from Eureka Productions’ “Graphic Classics” series.

(First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Saturday, October 27, 2012 ( 10/27/2012 08:41:00 PM ) Bill S.

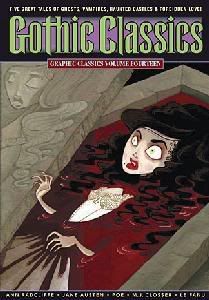

The new set, Halloween Classics The collection features five adaptations, one of which proves to be from a surprising, non-literary source. Two of the tales, Washington Irving’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and H.P. Lovecraft’s “Cool Air” are perhaps the most familiar while works by Mark Twain (the comic “A Curious Dream”) and Arthur Conan Doyle (“Lot No. 249”) prove more obscure, though I do recall seeing a modernized version of the latter in the movie spin-off of Tales from the Darkside. The fifth adaptation takes from movie history itself, a graphic story retelling of the German silent The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The stories throughout prove solid. Ben Avery and Shepherd Hendrix’s “Sleepy Hollow” reminded me of elements of the story (most particularly relating to the character of story patsy Ichabod Crane) that I’d forgotten with the Disney cartoon version as my primary prior recollection of Washington Irving’s tale. Antonella Caputo and Nick Miller’s “A Curious Dream” is a suitably cartoonish adaptation of a minor but amusing slice of Twain, while both Pomplun and Simon Gane’s version of the mummy story “Lot No. 249” and Rod Lott/Craig Wilson’s work on “Cool Air” both succeed in capturing their author’s respective voices. To these eyes, Wilson’s visualization of Lovecraft’s darkly anxious and xenophobic world is especially convincing. But the collection's highlight proves editor Pomplun and cartoonist Matt Howarth’s version of “Caligari,” which I believe is this series first adaptation outside of the printed page. The duo brings that stylized classic to life in a way, I suspect, that proves more emotionally accessible than the original German silent. If the color comic proves visually less expressionistic than the original black-and-white film, Howarth still manages to convey its essential strangeness, most memorably in a sequence where a sinister somnambulist carries the damsel-in-distress over the rooftops of the town. After this finale, all that’s left to cap this Halloween celebration is for our horror host Merwin to rip off his mask and reveal the hideous ghoul within -- which of course he does. The Crypt Keeper would be cacklingly proud. (First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Monday, September 24, 2012 ( 9/24/2012 05:49:00 AM ) Bill S.  Pomplun’s practice may drive more anal retentive collectors crazy (there are four editions of Eureka’s debut volume, Edgar Allan Poe, though I don’t know if all of these have slightly different contents), but those who came to this series late probably won’t be bothered by it, nor will those school libraries, I suspect, with earlier editions that have been much thumbed by young readers. For most moderately literate Americans, Stevenson is primarily known for his rousing boys’ adventure books (Island, Kidnapped), his children’s poems and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Both Long John Silver and the villainous Edward Hyde are given their due in this book, alongside a series of short verses and fables illustrated by the likes of Maxon Crumb, Shary Flenniken, Hunt Emerson, Roger Langridge and Johnny Ryan, plus an exquisitely rendered version of “The Bottle Imp” by Lance Tooks. The fables prove especially fascinating as they show the writer in a much more witty and cynical mode than his Child’s Garden of Verses voice. Tales like the Langridge illustrated “Sick Man and the Fireman” almost read as if they fell out of Graphics Classics’ Ambrose Bierce or Mark Twain collections. The fables are all fine, though to my eyes the peak pieces belong to GC regulars Langridge, Flenniken, Emerson and Tom Neely, whose rubbery art recalls some of the classic screwball comic strip artists of earlier decades. Two fables, interestingly, hinge on characters punished for either being a fool or consorting with fools. For a certain breed of Victorian intellectual, apparently, being a fool was a greater character deficit than being a sinner. The adaptations of Stevenson’s more familiar works are variably successful. Writer Alex Burrows and artist Scott Lincoln’s version of Treasure Island comes across too cleanly cartoonish to convey the grubby villainy of its pirates and their reprobate leader Long John Silver. (For me in part, this is due to the still-remembered 1934 and 1950 movie takes on the tale that featured Wallace Beery and the iconic Robert Newton in the role of Silver -- some memories are tough to surmount.) Burrows’ treatment of the story captures all the novel’s high points, though, so hopefully this version will spur new young readers into checking out the original.

The strongest of the longer adaptations proves Lance Took’s adaptation of the fantasy, “The Bottle Imp,” which effectively utilizes the writer/artist’s sinuous linework to capture the story’s South Seas island cast. Since the writer himself spent his last days in the tropics (as depicted in Mort Castle and Chad Carpenter’s comic bio of RLS), concluding this volume with “Imp” proves a smart editorial decision -- exiting in a setting that the writer grew to know and love as well as wrapping up this fine collection with one of its strongest entries. (First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Thursday, March 22, 2012 ( 3/22/2012 06:30:00 AM ) Bill S.  The relative “newness” of the material (much of it written in the twenties and thirties) proves to be one of the collection’s biggest strengths. Where most educated Americans know “The Tell-Tale Heart” (if only from more than one parody on The Simpsons), they’re less likely to recognize Robert W. Bagnell’s horrific revenge tale, “Lex Talionis,” even if its core plot idea has been later used on more than occasion. The material in Classics ranges from fiction to poetry to philosophical ruminations on the nature of race. Dubois’ “On Being Crazy” provides a strong example of the latter, a set of dialogs between the narrator and a quintet of racist Southern folk who repeatedly turn him away. Artist Kyle Baker wittily captures the narrator’s rueful recognition of the reality surrounding him even as he acknowledges the insanity of it. Many of the adapted short stories here prove highly allegorical: Ethel M. Caution’s “Buyers of Dreams,” for instance, depicts three women who enter a mystical shop to purchase a dream. The first two seek baubles and career; the “wise” one chooses love and family. (You can definitely tell the piece was written in 1921.) Other stories inevitably prove didactic: opener “Two Americans” by Florence Lewis Bentley, puts white and black Southern soldiers in the Great War for a not-unexpected lesson about the importance of putting aside racial differences against a common enemy. Trevor Von Eedon, an artist best known for his work on super-hero titles, makes his debut in “Graphic Classics,” and it’s a welcome addition. More startling to modern readers, perhaps, are several dialect pieces (Hurston’s “Lawin’ and Jawin’” and “Filling Station,” Leila Ames Pendleton’s “Sanctum 777 NSDCOU Meets Cleopatra”) that at times read like a couple of white radio comedians playing Amos and Andy. (Looking at “Lawin,’” for instance, I could help conjuring up the image of Sammy Davis Junior strutting before the teevee cameras on Laugh-In.) The book’s invaluable author notes state that writers like Hurston saw some critical disrepute for a time due to their reliance on heavy dialect, and I have to admit to having some mixed reactions to the stories featuring it myself. Love Milton Knight’s cartoony art on “Filling Station,” though. Where this trade paperback collection really shines is in its moodier entries: co-editor Took’s evocative reworking of Alice Dunbar Nelson’s “Carnival Jangle,” a tale of murder at the Mardi Gras, and Matt Johnson/RandyDuBurke’s version of Jean Toomer’s “Becky,” both linger long after they’ve been read. The latter, a story of a young white girl shunned by all in her community for giving birth to bi-racial sons, is especially effective. With the exception of its opening panels, the whole piece focuses on the ramshackle cabin where the title figure is exiled, observing its unknowable isolated protagonist from a distance. A very effective treatment of this disturbing story: artist DuBurke’s green-washed panels add to its considerable melancholy. Tom Pomplun’s Eureka Productions has been putting out these well wrought literary comics collections long enough (this is volume 22 in the series) that it’s been easy to take ‘em for granted. Here’s hoping that the distinctness of African-American Classics sparks renewed interest in this enjoyable series of trade paperbacks. (First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Tuesday, August 30, 2011 ( 8/30/2011 09:57:00 PM ) Bill S.  CONQUEROR WORMS AND PESTULANT REVELERS: It makes sense that American author Edgar Allan Poe would have been the first writer to receive a “Graphic Classics” collection. His fiction has inspired a vast amount of adaptations over the years, including prior comics art retellings -- so many that one suspects a sizable majority are more familiar with the adaptations than they are the prose original originals. To a certain extent, this is understandable: Poe’s voice -- for all that he helped to kick-start genres like the formal detective story -- was very much a 19th century one. I remember it being fairly daunting myself when I first tried tackling it in the fifth grade, though once you got to the good grisly stuff, the effort seemed worth it. CONQUEROR WORMS AND PESTULANT REVELERS: It makes sense that American author Edgar Allan Poe would have been the first writer to receive a “Graphic Classics” collection. His fiction has inspired a vast amount of adaptations over the years, including prior comics art retellings -- so many that one suspects a sizable majority are more familiar with the adaptations than they are the prose original originals. To a certain extent, this is understandable: Poe’s voice -- for all that he helped to kick-start genres like the formal detective story -- was very much a 19th century one. I remember it being fairly daunting myself when I first tried tackling it in the fifth grade, though once you got to the good grisly stuff, the effort seemed worth it.“Graphic Classics” editor Tom Pomplun has returned to this most fertile of storytellers for the 21st volume in his still strong trade paperback series. Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery (Eureka Productions) contains ten of Poe’s short stories plus a smattering of poems. The tales run from the familiar (as with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” a work which provided a template for the detective yarn; “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Masque of the Red Death”) to the obscure (darkly comic “King Pest,” “Berenice,” and “The Man of the Crowd” among them). Editor Pomplun and his collaborators all strive to remain true to the author’s distinct narrative style, and, in general, they succeed. Highlights in this collection of gothic treats include Pomplun and Nelson Evergreen’s “Berenice,” which takes a potentially ludicrous concept (haunted by the image of a dead love’s teeth!) and invests it with a convincing level of dread; Antonella Caputa and Anton Emdin’s version of the bleakly comic “King Pest,” which benefits from its Punk! magazine cartooning; and Ron Sutton’s modernized version of “The Tell-Tale Heart,” which reconfigures its mad narrator as a girl punk. (Hey, if Lisa Simpson can hear “the beating of his hideous heart,” so can our mohawked anti-heroine.) Almost as strong are Pomplun and Michael Manning’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” and Ron Lott and Lisa K. Weber’s “Hop Frog,” both of which faithfully reconstruct their stories without quite attaining their full level of horror. Back when I looked at an edition of Pomplun’s first series of E.A. Poe tales, I remember commenting about the fact that the collection didn’t include any of the writer’s “ratiocinative” tales. After reading and reacquainting myself with “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” though, I can understand the delay. While it may be a historically significant genre piece, Poe’s "Rue Morgue" proves rather tedious in comics format. Its prototype hero August Dupin and its Watson-esque narrator never are never quite interesting enough to hold this far-fetched mystery, and while Caputo and artist Reno Marquis capture the material, the fact remains that it’s hard to make two guys standing in a room and talking about deductive reasoning all that riveting. Perhaps if Marquis was a more stylized illustrator (as with the woodcut-inflected Brad Teare in the otherwise trifling “The Man in the Crowd”) the results might have proven more memorable. It’s the shorter poems that provide their respective artists the most room to fly beyond the fringe, whether it’s Maxon Crumb providing a Basil Wolverton-y illo for “Alone,” Neale Blanden’s suitably surreal cartooning of “A Dream within a Dream” or Malaysian artist Leong Wan Kok staging a grisly interpretation of “The Conqueror Worm.” If the stories remain the prime draw for these “Graphic Classics” volumes, the poems add an art comics feel to the package that’s especially apt for this magnificently depressive genre pioneer. (First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Wednesday, April 13, 2011 ( 4/13/2011 06:36:00 AM ) Bill S.  “MEDDLER, WE HAVE A LAW HERE SOMETHING DIFFERENT FROM WOMAN’S WHIM!” The 20th volume in editor Tom Pomplun’s series of “Graphic Classics” collections, Western Classics (Eureka Productions) boasts the appearance of two long-established comics names. Al Feldstein, known for his years as the artist/writer/editor for EC and editorship of Mad magazine, is represented by a lovely color illo accompanying a piece by cowboy poet Arthur Chapman, while Dan Spiegle, who once drew the “Hopalong Cassidy” comic strip, makes a substantial showing with a 16-page adaptation of an early Hoppy short story. “MEDDLER, WE HAVE A LAW HERE SOMETHING DIFFERENT FROM WOMAN’S WHIM!” The 20th volume in editor Tom Pomplun’s series of “Graphic Classics” collections, Western Classics (Eureka Productions) boasts the appearance of two long-established comics names. Al Feldstein, known for his years as the artist/writer/editor for EC and editorship of Mad magazine, is represented by a lovely color illo accompanying a piece by cowboy poet Arthur Chapman, while Dan Spiegle, who once drew the “Hopalong Cassidy” comic strip, makes a substantial showing with a 16-page adaptation of an early Hoppy short story.If the presence of these two old pros serves to hint that the contents in the new graphic storytelling collection will be a trace more visually conservative than, say, some of the selections in Gothic Classics, that’s arguably in line with the material being adapted this time. Pomplun and collaborators are tackling some fairly straightforward tales of the American West, after all, not opening up the deranged nightmares of an E.A. Poe. That’s for the next “Graphics Classics” set. The book opens with a retelling of Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage, a core genre work that remains the popular western writer’s best-selling book. As adapted by Pomplun and illustrator Cynthia Martin, the piece is a respectful take on this dense western work, though at times the multiple threads from the novel lead to some dialog-heavy pages. Scripter Pomplun downplays one of the novel’s most striking features -- its use of Mormons as story villains -- the theme is still there for those who know to look for it. If Martin’s renderings of the cast and setting may occasionally look a bit too pristine, it’s in keeping with the early 20th century novelist’s style. A grittier, unshaven take on the genre can be found, surprisingly, in Tim LaSiuta and Dan Spiegle’s Hopalong Cassidy tale. For those who grew up on the clean-cut movie and TV versions of the character, this 1913 Clarence E. Mulford tale is a revelation: the original version of the character was rough-hewn and gimpy legged. Mulford’s “The Holdup” is a simple yarn about Hoppy and friends’ disruption of a train robber, but if the story is pretty basic, Spiegle’s art (which at times brought of memories of Jean Giraud’s magnificent Lieutenant Blueberry comics) is not. Ninety years old, and, damn, can that man draw. If, to these eyes, these two pieces are the highlights in Western Classics, the rest of the contributions are engaging. Ben Avery and George Sellas’ take on one of Robert E. Howard’s comic westerns is breezily cartoony, in keeping with the original, while Trina Robbins and Arnold Arre’s remake of Gertrude Atherton’s “La Perdida” (as with “Purple Sage,” a tale centering on a young beauty being lusted after by an older man) benefits from a strikingly visualized conflagration finale. David Hontiveros and Reno Maniquis’ version of Bret Harte’s “The Right Eye of the Commander” comes across a bit text-heavy, but Maniquis’ art beautifully captures the story’s western gothic tone. The book ends on two somewhat forlorn notes: “The Last Thundersong,” by John G. Neihart (adapted by Rod Lott and Ryan Huna Smith), where the author of Black Elk Speaks reflects on spiritual belief and the decimation of Native American culture, and Willa Cather’s “El Dorado” (Rich Rainey and John Findley) which charts the life and death of a Kansas wilderness town as seen by a stranded settler. A far cry from the more spirited genre works of Grey or Howard, but inarguably part of the American western experience. One of the consistent strengths of this series has been editor’s Pomplun’s ability to pull in both familiar and obscure works under each volume’s title theme -- and this entry is no exception. As with last year's Christmas Classics, Pomplun and his collaborators are playing at the top of their game. (First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Friday, December 10, 2010 ( 12/10/2010 10:06:00 PM ) Bill S.  “THINK OF THE FRIO KID PLAYING SANTY!” Tom Pomplun’s Graphic Classics series goes seasonal with its 19th volume, Christmas Classics (Eureka Productions), and as in earlier volumes in this well-produced series of classic lit adaptations, the new color comics anthology contains a strong blend of familiar and lesser known works by American and British writers. “THINK OF THE FRIO KID PLAYING SANTY!” Tom Pomplun’s Graphic Classics series goes seasonal with its 19th volume, Christmas Classics (Eureka Productions), and as in earlier volumes in this well-produced series of classic lit adaptations, the new color comics anthology contains a strong blend of familiar and lesser known works by American and British writers.After a one-page intro reprinting a Letter from St. Nicholas written by Mark Twain (more charming than satiric), the book opens with its two most familiar Christmas works: an adaptation of Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” and Clement Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” The first, adapted by Alex Burrows and Micah Farritor, proves serviceable; though the writer and artist don’t really add much to this holiday chestnut save for the image of Marley’s ghost’s jaw dropping off of his face in mid-warning. Still, the version remains true to Dickens’ vision and thankfully doesn’t stint on some of the grimmer images so essential to the story. Florence Cestac’s big-nosed illos on the equally familiar Moore poem are wholeheartedly cartoony, though, in this case the poem’s familiarity works against the graphics in more than one panel. When our narrator is roused from bed by the rooftop clatter, for instance, the sharp-eyed reader can’t help wondering, “Isn’t this guy supposed to be wearing a nightcap? And where’s mama?” It’s okay to make the art cartoonlike, just stay true to the limited text, okay? From there, though, the selections in Classics grow increasingly more surprising. Rich Rainey and Hunter Emerson’s “Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle” takes a lightweight Sherlock Holmes adventure and reminds us that even classic literary series characters weren’t immune to the demands of a holiday adventure. British artist Emerson, who can sometimes get pretty free-wheeling in his artwork, plays it relatively straight with this outing, though doubtless some Baker Street Irregulars will take issue with the exaggerated features on his great detective. O. Henry’s Christmas romance, “A Chaparral Christmas Gift,” is handled much more conservatively by artist Cynthia Martin, which works for this none-too-surprising western yarn. (The writer’s better known offering, “The Gift of the Magi,” has already been adapted in a Graphic Classics O. Henry collection.) Editor Pomplun, who has handed himself the task of adapting the more obscure works, handles this and the next three tales, the most visually outlandish being an adaptation of Willa Cather’s “Strategy of the Werewolf Dog,” the story of a Grinch-y attempt to destroy Christmas that amazingly doesn’t end with the villain’s reformation. Dutch former undergrounder Evart Geradts renders this tale in a heavily stylised manner, like a children’s book on acid, which leavens Cather’s dark fantasy somewhat. Definitely an odd little tale. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s jazz age short story, “A Luckless Santa Claus,” comes across more than a little contrived in its comedy. The story of a well-to-do scion who is challenged by his girlfriend to give away $25.00 in one night to less fortunate New Yorkers, the story’s central premise may strike many readers as unbelievable in these fiscally strapped times (each time our hero attempts to surreptitiously give some money away, the recipients return it), though Simon Gane’s art captures the snow-strewn period city setting nicely. With Fitz-James O’Brien’s holiday horror tale, “The Wondersmith,” Pomplun and artist Rick Geary end the book on a suitably imaginative note. The story of a wicked sorcerous trio who plot to send killer dolls out to slaughter Christian children, the story is rendered with wit and conviction by Geary. The artist, best known for his own series of graphic novels examining famous 19th and 20th century murders, is a master of period melodrama, and he’s definitely in his element here. At one point, when the title central miscreant gloats about his nasty plans, you find yourself wishing that his moustache were longer so he could start twirling it. The dastard’s evil War on Christmas is defeated, of course -- by a noble hunchback bookseller, a waifish organ grinder and her pet monkey -- because you can’t make a holiday story like this too grim, can you? Often, when it comes to Yuletime entertainments, the creators count too much on the good will engendered by the season to cover half-assed careless work. That is not the case with this collection here, though, which represents Pomplun and many of his usual collaborators working to their storytelling strengths. It’s one of the solidest Graphic Classics sets to date. (First published on Blogcritics.) Labels: classics illustrated # |Sunday, December 20, 2009 ( 12/20/2009 09:12:00 PM ) Bill S. ”THERE IS TRUTH IN IT, JO; THAT’S THE SECRET!” That editor Tom Pomplun’s latest Graphics Classics collection, Louisa May Alcott (Eureka Productions), should come out in time for Christmas is smart scheduling. Alcott’s most beloved work, Little Women, memorably opens up on the holiday, as the four March sisters and their mother strive to celebrate the season while their father is away at war, and this latest volume in Pomplun’s series of graphic adaptations of classic lit likewise opens with the same scene. Women, which is featured in a 48-page adaptation, is none too surprisingly given cover placement on this collection, and Anne Timmons’ image of thoughtful would-be writer Jo March working on her latest manuscript could also stand in as an image of Alcott herself. (Little Women famously contains a lot of autobiographical elements.) Scripter Trina Robbins and Timmons’ color comics version of this much-adapted novel is a smart retelling, tamping down the original work’s more openly didactic moments in favor letting the March girls’ stories speak for themselves. The approach presents Alcott’s work in a good light. The only off note is the comic German dialect given to Jo’s eventual suitor Professor Bhaer. While its use in the adaptation is faithful to the author, I’ve always thought it a detriment to this courtly character. Despite this glitch, Robbins and Timmons prove the ideal duo for a sensitive adaptation of the book. Together, they share a sensitivity that suits Alcott’s blend of the feminine and feminist: the moment where Jo bursts into tears after selling her hair to raise money for her war-wounded father, for instance, is deftly and sweetly handled. If the comics version focuses on Jo more at the expense of the other little women, that’s not unusual for these adaptations: she’s always been the most dynamic character in these books, anyway. Women spurred three sequels, but that wasn’t the full extent of Alcott’s writings. Many of her youthful works, frequently written under the pen name of “A.M. Barnard,” are blood-and-thunder gothics of the type Jo herself would’ve written. The Graphic Classics set happily includes two of these lesser-known dark tales. The first, Alex Burrows and Pedro Lopez’s adaptation of the short “Lost in A Pyramid,” is a short and effective story of a mummy’s curse, while the 42-page A Whisper in the Dark proves an enjoyable damsel-in-distress tale featuring a wicked uncle, an inheritance scheme and a heroine who is drugged and driven mad by her tormentors. Though Antonella Caputo and Arnold Arre’s version takes a few too many pages for the dire deeds to commence, once they do, the results prove moodily suspenseful, with Arre skillfully charting the heroine’s descent into despair and madness. As a writer of “disreputable” genre fiction, Alcott was much more rousing than she was crafting her more domesticated March books. It’s great to see this lesser known Alcott storytelling being highlighted here. The remaining shorter pieces further display her range as a writer. Rod Lott and Molly Crabapple’s “The Rival Prima Donnas” treats this tale of a deadly romantic rivalry with a trace of a wink that almost undermines its grim ending; editor Pomplun and Mary Fleenor’s “Buzz” utilizes the artist’s stylized edgy renderings to convincingly evoke one woman’s solitude in the big city; while Pomplun and Shary Flenniken’s “The Piggy Girl” wittily makes good use of the cartoonist’s skillful evocations of kidhood. The only arguable lull comes with Lisa K. Weber’s illos for the poem “Lay of the Golden Goose.” Weber’s illustrations, placed alongside Alcott’s poetry are suitably storybooky, but the poem itself is much too slight. The eighteenth volume in editor Pomplun’s Graphic Classics series, Louisa May Alcott is one of the strongest entries yet. Not only does it contain a solid selection of modern comic art, it provides an eye-opening overview of an author most readers only know as the creator of the ultra-girly Women. Reading the opening chapter to the March saga, with its comic depiction of a disastrously performed Christmas play, I couldn't help thinking that our gal Jo'd be delighted to see one of her Christmas melodramas recreated in an anthology like this. Labels: classics illustrated # |Friday, May 29, 2009 ( 5/29/2009 11:02:00 AM ) Bill S.  "I HAVE SEEN THEM IN THE TWILIGHT." Considering the material adapted in the newest (Volume 17) edition of Tom Pomplun's Graphic Classics series, Science Fiction Classics, I started idly wondering whether a better title might be "Scientifiction Classics." "I HAVE SEEN THEM IN THE TWILIGHT." Considering the material adapted in the newest (Volume 17) edition of Tom Pomplun's Graphic Classics series, Science Fiction Classics, I started idly wondering whether a better title might be "Scientifiction Classics."That ungainly term, first floated in 1926 with the publication of Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories, arguably comes closer to the early sci-fi exercises presented in comics form here -- especially a more technocratic work like Jules Verne's "In the Year 2889" -- in part because it implies a stronger emphasis on the science component over storytelling. You can see this imbalance in Verne's tale, as well as a one-page Hunt Emerson illustrated comic of Hans Christian Anderson predictions "In A Thousand Years." Neither piece has much in the way of character or story conflict. To a slightly lesser extent, the emphasis on ideas also extends to pieces like Arthur Conan Doyle's "The Disintegration Machine" and E.M. Forster's classic cautionary "The Machine Stops." Still, even in the book's potentially driest offering, editor Pomplun has the smarts to couple it with a sprightly cartoonist like Angry Youth Comix creator Johnny Ryan. And where the didactic "Machine Stops" might have been deadly in less visually inventive hands, Ellen Lindner's expressive cartooning and coloring keeps things interesting. This is the first Graphic Classics volume to feature color in all of its stories, and in Lindner and Ryan's pieces, it is smartly deployed. In the latter case, the bright flat colors enhance the Hanna-Barbera cartoonishness of Ryan's art; in the former, the more subdued coloration suits the washed out decadence of Forster's doomed dystopia. The cover story, a 48-page version of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds, is the book's first draw, of course. Wells' classic has been adapted into comics before -- the Classics Illustrated version from 1955 was my first introduction to the story -- while its status as a public domain work has inspired more than one comic company's attempt at picking up where the story ends. The Graphic Classics version, scripted by Rich Rainey and illustrated by Micah Farritor, proves closer to Wells' original intentions than the Eisenhower Era adaptation: a once bowdlerized scene featuring a hysterical curate has been reinstated in the story, while the narrator protagonist's less-than-noble moments are also unapologetically depicted. The reinsertions strengthen this retelling of Wells' familiar s-f story significantly. Less familiar, though no less influential as an early s-f story, is Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1934 "A Martian Odyssey," generally acknowledged to be the first of its kind to depict an alien character whose thought processes are distinctly different from that of humans. Adapted by Ben Avery and effectively illustrated in a whimsical zap gun style by George Sella, it entertainingly captures Weinbaum's voice and distinct sense of wonder: "scientification" at its greatest. Two other tales don't fare as well, in large part due to the original sources' slightness. Tod Lott and Roger Langridge's version of Arthur Conan Doyle's Professor Challenger story, "The Disintegration Machine," is well presented, though Doyle's original story -- which basically involves the egotistical Challenger's besting a grotesque mad scientist in the simplest fashion -- is fairly weak. Antonello Caputo and Brad Teare's retelling of Lord Dunsay's "The Bureau d'Exchange de Maux" has an appealingly dark woodcut look, though it's debatable whether the actual story fits under the science-fiction rubric. In it, Dunsany's narrator enters a shop where customers exchange a personal "evil or misfortune" for that of another's. Our hero does this, of course, exchanging a long-held phobia for a fresh one, though Dunsany doesn't take this basic conceit much further. As a full collection of early s-f, Pomplun's volume is the most consistently accessible of Graphic Classics' genre collections that I've seen to date. (In contrast, consider the overly wordy adaptation of "Northanger Abby" in Gothic Classics.) Next up, a book devoted to adaptations of Louisa May Alcott. I wonder if it'll include any of her scandalous A.M. Barnard thrillers? It's been ages since I've read 'em, but I seem to remember they were considerably zippier than Jane Austen. Labels: classics illustrated # |Thursday, March 12, 2009 ( 3/12/2009 05:50:00 PM ) Bill S. "A GREAT CRIME AGAINST SOME UNKNOWN GOD" Unlike the recently revamped Graphic Classics devoted to the works of Ambrose Bierce, Tom Pomplun's newest anthology of modern "Classics Illustrated" comics skips the short stuff in favor of four longish adaptations. Featuring graphic versions of Wilde's only novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, "The Canterville Ghost," "Lord Arthur Savile's Crime" and the play Salome, the sixteenth volume in this series does a bang-up job capturing the Victorian author's distinct voice. In this, it is perhaps one of the most successful entries in Graphic Classics series to date. The book opens with its cover story, Alex Burrows and Lisa K. Weber's version of Dorian Gray. The densest of the four works adapted, it's a tale that's already sparked more than comic book adaptation (including one produced by Marvel Comics). Burrows and Weber's take doesn't stint on the original work's upper class-based decadence -- the artist captures the title character's sleepy-eyed beauty convincingly, while Burrow's script has just enough loaded innuendo to make the book's gay subtext sufficiently clear-cut. (Wilde himself famously tamped down the homoerotic aspects of his story between first and second editions of its publication.) If the comic version doesn't fully convey the original's moody gothic elements, it smartly nails Wilde's trenchant critiques of the aesthete's elevation of artistry over humanity. Even more successful are the adaptations of "Ghost" and "Crime." The former, done by Antonello Caputo and Nick Miller is the most overly funnybookish -- artist Miller even draws two twin boys to resemble the Katzenjammer Kids -- while the latter utilizes heavy-handed brush strokes (courtesy of Stan Shaw) to emphasize the source's darker comedy. "Ghost," which describes the clash between an old-fashioned British haunt and a very "republican" American family, seems particularly current, though the unpunished antihero Lord Savile demonstrates just how ahead of his time Wilde could be. The book concludes with editor Pomplun and Molly Kiely's adaptation of the Biblical tragedy "Salome." Pomplun relies heavily on the play's original dialog, but in this case the decision has mixed results as Wilde's attempt at dramatizing the events leading up to the beheading of John the Baptist has more than its share of wooden lines. Kiely's graphics recall Beardsley (who famously illustrated the play on its English publication) in her use of blacks and whites, though they're by no means as explicit as the Beardsley's original art nouveau illos. The final pages, where the villainous Salome holds and kisses the severed head of the martyr, are agreeably horrific, if not as memorable as Beardsley's famous illustration of the dancer holding John's head on a blood-drenched table. I can't help wondering whether Wilde the Aesthete would've sniffed that the artist's panel-to-panel depiction of character was a trace too loose, though. Still, the adaptation remains true to Wilde's tone and outlook as do the other three pieces in this solid collection. Next announced title in the series is a genre-based collection of Science-Fiction Classics set for June release. Just the thing to read between volumes of the new League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series. Labels: classics illustrated # |Friday, November 28, 2008 ( 11/28/2008 05:20:00 PM ) Bill S.  THE AMBROSE COLLECTION: If ever there was a writer more aligned with the sensitivities of today's young cartoonists, it's Ambrose Bierce. The journalist and author, a master of the darkly cynical, provides plenty of good material for the grim at heart, and the newly revised and reissued Graphic Classics (Eureka Productions) devoted to his works ably makes this case. Planted with the middle of the 144-page book is a selection of "Bierce's Fables," one- and two-page pieces done by twenty different cartoonists (among them: onetime Air Pirates Shary Flenniken and Dan O'Neill, P.S. Mueller and alt cartoonists Roger Langridge and Johnny Ryan) – each one of which lovingly recreates Bierce's caustically comic take on the human condition. THE AMBROSE COLLECTION: If ever there was a writer more aligned with the sensitivities of today's young cartoonists, it's Ambrose Bierce. The journalist and author, a master of the darkly cynical, provides plenty of good material for the grim at heart, and the newly revised and reissued Graphic Classics (Eureka Productions) devoted to his works ably makes this case. Planted with the middle of the 144-page book is a selection of "Bierce's Fables," one- and two-page pieces done by twenty different cartoonists (among them: onetime Air Pirates Shary Flenniken and Dan O'Neill, P.S. Mueller and alt cartoonists Roger Langridge and Johnny Ryan) – each one of which lovingly recreates Bierce's caustically comic take on the human condition.Series editor Tom Pomplun balances the quick and the snarky (including an abridged version of Bierce's "Devil's Dictionary" with gloriously elaborate full-page graphics by the Residents' artist-in-residence Steven Cerio) with some of the writer's tales of the supernatural. New to this edition are adaptations of two horror tales, "The Damned Thing" and "Moxon's Master," and a piece adapted by Bierce from an original German short story, "The Monk and the Hangman's Daughter." The last, scripted by Antonella Caputo and illustrated with moody gray-tones by Carlo Vergara, is an especially fine bit of Bierce-ian bleakness. A tale of romantic obsession, religious madness and murder, it captures those elements of human hypocrisy and self-deception that were fodder for the American writer. Vergara's rendering of the story's climax, where its narrating protagonist slays the object of his affections to "save" her soul, is overwrought and restrained at once. The remaining new stories aren't as effective. In the case of "The Damned Thing," the fault perhaps lies in the source. Though Bierce's central concept (of a creature whose coloration puts it beyond human visual capacity) has been one that's sparked plenty of later day horror writers, the story itself is no great shakes. "Master" is the stronger entry, though the voluminous word balloons and narrative boxes that writer/artist Stan Shaw utilizes in his comic adaptation prove more than a little daunting. Shaw's expressionistic art is engaging but not enough to keep the comic from being weighted down in wordiness. All three of the new pieces take a visually serious approach to the material – as does Mark A. Nelson in an elegant adaptation of the Arizona ghost story, "The Stranger" – though several of the book's other contributors provide a lighter touch to Bierce's short fictions. Particularly strong is Michael Slack's stylized artwork on the illustrated story, "The Hypnotist," an unflinching piece narrated by an unapologetic murderer that might have been unbearable if it'd been rendered more realistically. Same goes for Anne Owens' adaptation of "Oil of Dog," which is rendered in a buoyant cartoon gothic style that looks like something the Tim Burton of Sweeney Todd might have lensed. Owens' adaptation is nearly as wordy as "Moxon's Master," but because she letters her longer passages outside the panels, giving them less of a constricted feel, the story reads more smoothly. Pomplun also includes a cartoonishly irreverent four-page consideration of the life of Bierce by Mort Castle and Dan E. Burr, which itself proves as entertaining as any of the tales in this book. The adventurous Bierce famously disappeared in Mexico in 1913 or '14, and "The Disappearance of Ambrose Bierce" examines the various theories put forth to explain this slice of American literary history – including Charles Fort's magnificently bizarre theory that the man of letters was abducted by aliens looking to collect men named Ambrose. Bierce, one suspects, would've been amused both by Fort's wackiness and the comic here exposing it . . . Labels: classics illustrated # |Saturday, June 14, 2008 ( 6/14/2008 01:23:00 PM ) Bill S.  DREAMWORLDS: The first real adaptation of Mary W. Shelley's Frankenstein that I remembering seeing was a Classics Illustrated comic owned by a collecting buddy. Though originally printed in the forties, the comic (adapted by Ruth Roche, Robert Heywood Webb & Ann Brewster) was reprinted with a different cover in the fifties, which is when my young boy self would've discovered it. Truer to the book than the original James Whale Universal Pictures version, it contained an image that's still retained by my mind's eye: a panel showing Victor Frankenstein's disastrous wedding night. It was a moment that lingered in my boyish imagination and contributed toward spurring this post-EC reader's love of horror comics. DREAMWORLDS: The first real adaptation of Mary W. Shelley's Frankenstein that I remembering seeing was a Classics Illustrated comic owned by a collecting buddy. Though originally printed in the forties, the comic (adapted by Ruth Roche, Robert Heywood Webb & Ann Brewster) was reprinted with a different cover in the fifties, which is when my young boy self would've discovered it. Truer to the book than the original James Whale Universal Pictures version, it contained an image that's still retained by my mind's eye: a panel showing Victor Frankenstein's disastrous wedding night. It was a moment that lingered in my boyish imagination and contributed toward spurring this post-EC reader's love of horror comics.Shelley's classic is the cover feature of the latest Tom Pomplun-edited Graphic Classics trade paperback (Volume Fifteen in the series), Fantasy Classics. And though scripter Rod Lott remains as true to the source novel as the earlier Classics Illustrated did, I'm not sure this latest comics adaptation would work as well on my former young boy self. At issue is artist Skot Olsen's big-foot cartooning style, which works against the unflinching horrors being depicted. When we're shown a young seemingly flattened from his encounter with the Frankenstein monster, for instance, the effect is more Wile E. Coyote than gothic. The adaptation is preceded by a prologue recounting the well-known origins of Shelley's seminal novel, and looking at Mark A. Nelson's more conservative "realistic" art, I can't help wishing he'd been given the full assignment instead of just its footnote. To my eyes, Olsen's caricatures are more apt for a more whimsical fantasy, such as the volume's retelling of L. Frank Baum's "The Glass Dog," than it is this groundbreaking work of horror s-f. It occurs to me that someone who has raved in the past about the hyper-stylized art of a horror manga artist like Hideshi Hino may have no business complaining about cartoony art, but I'm comfortable with the contradiction. I do wonder if a young boy reader reared on manga conventions would find it easier than me to get into this new version, though. Apart from two one-page illustrated poems, the new volume contains three more classic adaptations: the first, Lance Took's version of Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Rappaccini's Daughter," is more an illustrated story than a comic, though his artwork has such a sensual elegance to it that I love looking at his images even as my eye resists the plethora of text surrounding 'em. Antonella L. Caputa & Brad Teare's version of Baum's "Glass Dog" is an amusing take on one of the Wizard of Oz writer's more obscure comic fables, though the stand-out story in this volume has to be Ron Avery & Leong Wan Kok's version of H.P. Lovecraft's "Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath." Unlike most of his better-known horror fiction, "Kadath" is a fantasy tale devoted to the sleeping wanderings of Randolph Carter, who is seeking a mysterious city located in the unknown parts of a dreamland. His voyages take him through a landscape filled with talking cats, undead ghouls and dwarflike creatures called Zoogs, culminating in a face-to-face with a massive tentacled god named Nyarlathotep. As a fiction, Lovecraft's work doesn't have the impact of his great horror works - it meanders too much to be as effective - but Malaysian artist Kok does a wonderful job of capturing Carter's dream world. Unlike Olsen, he balances stylization with enough realistic touches to keep the reader in the story. I can see some young reader following Avery & Kok's version of Lovecraftian love into further explorations - perhaps the Graphic Classics volume devoted to the man's eldritch horror tales? Labels: classics illustrated # |Sunday, May 04, 2008 ( 5/04/2008 09:30:00 AM ) Bill S. "YOU MESMERISED THE MESMERISER!" Because I currently live some two hours from the nearest comic book store in Tucson, this year's Free Comic Book Day proved a pretty spare occasion for me. The only title I was privy to was a sampler sent by Tom Pomplun, editor and publisher of the Graphic Classics series. A 64-page set of black-and-white graphic adaptations, the floppy contains works by Edgar Allan Poe, Ambrose Bierce, Lord Dunsany, Arthur Conan Doyle and Mary Shelley. Like the larger trade paperback collections that the sampler serves to promote, the collection works to demonstrate just how difficult a good comic adaptation of "classic" literature can be. Too tight an allegiance to the original written work, and you don't have comics, but an illustrated Reader's Digest abridgement, yet wander too far from the material and you run the risk of losing the writer's voice. The five works included in the FCBD set display the varying success even good solid professional writers and artists can achieve in this arena. The sampler opens with a cover story adaptation of Poe's "The Black Cat" written by Rod Lott and illustrated by Gerry Alanguilan. Told in first person by its murderer/madman, it's a tempting story to overwrite, but Lott proves sparing with his narration, letting his artist carry the big shock scenes. (There's a half page panel of our wild-eyed protagonist strangling his wife that looks like it could have come off the cover of EC's Shock Supenstories.) The results effectively capture Poe's words and story without being overly beholden to the former. On the other side, however, rests Antonella Caputo and Anne Timmons' adaptation of Mary Shelley's romance "The Dream," which is so stuffed with the original work's florid narration that it overwhelms the comic. Timmons' art sweetly captures the air of 19th century romance (in more than one panel it reminds me of a more detailed Trina Robbins), but Caputo's unrestrained reliance on boxed narration ultimately proves too much. Alex Burrows and Simon Ganes' adaptation of Conan Doyle's "John Barrington Cowles" rests somewhere in between the Poe and Shelley tales. Though Burrows relies heavily on Doyle's own words, he knows when to let a simple silent panel suffice. I wasn't familiar with Doyle's tale of a literally mesmerizing young woman, but the Graphic Classics made me want to track it down. A big key to this 'un lies in Ganes' stylized art, which at times reminds me of Alex Nino. It neatly captures its sadistic heroine in all her seductively whip-wielding glory, even if the comic's ending comes across curiously flat. All three of these pieces are about the length of your usual single-story comic book (good value for the money, eh?) To round out the book, Pomplun includes two shorter pieces. Of these, Milton Knight's adaptation of the Lord Dunsany poem, "A Narrow Escape," proves the purest comic. Tossing out most of the poem altogether, Knight retells its comic vignette with pure cartoony vigor. I fell in love with Knight's style back when he was writing and penning a sexy black-and-white funny animal comic for Fantagraphics entitled Hugo, and I'm always cheered to see fresh work by the man. Possessed of a Fleischer-esque visual sensibility, Knight's work is about as far from the strictures of mainstream "Classic Comics" storytelling as you can get, but he still manages to remain true to Dunsany's characteristically sardonic tone. His place at the end of the sampler makes you wish that the rest of the comic book's adapters had just a little more of his audacity. Still, I see from the credits at the end of this sampler that Knight's work appears in eight of the paperback collections themselves, so it's clear publisher Pomplun knows when he's got a good thing. As a sample of its wears, the Graphic Classics floppy generally does the trick: it provides a fair sense of the line's material and approach - from the occasional stodgy retelling to more free-wheeling fare - and hopefully piques the interests of more than a few lit lovers out there. If you came to Free Comic Book Day looking to see the potential and diversity in the artform, chances are you appreciated this little giveaway. If you came looking to see what Marvel's offered to tie into the new Iron Man flick, you probably didn't even pick this comic off the freebie table in the first place. All in all, not a bad Free Comic Book Day for yours truly . . . Labels: classics illustrated # |Tuesday, December 25, 2007 ( 12/25/2007 04:09:00 PM ) Bill S.  "HE WAS A PRESBYTERIAN, AND HAD A MOST DEEP RESPECT FOR MOSES, WHO WAS A PRESBYTERIAN, TOO." After revising and reissuing two editions of its candlelit collections (Gothic Classics and Bram Stoker), editor Tom Pomplon's Graphic Classics series (Eureka Productions) has recently retooled its anthology of Mark Twain comic adaptations into a spanking new edition. To the untrained eye, this newest reissue may represent a considerable shift in tone: from the ominous trappings of sinister towers and dark deeds to the lighter voice of America's great humorous storyteller. But to those who know Sam Clemons beyond such crowd-pleasers as Tom Sawyer and Prince And the Pauper, it isn't such a big leap after all. "HE WAS A PRESBYTERIAN, AND HAD A MOST DEEP RESPECT FOR MOSES, WHO WAS A PRESBYTERIAN, TOO." After revising and reissuing two editions of its candlelit collections (Gothic Classics and Bram Stoker), editor Tom Pomplon's Graphic Classics series (Eureka Productions) has recently retooled its anthology of Mark Twain comic adaptations into a spanking new edition. To the untrained eye, this newest reissue may represent a considerable shift in tone: from the ominous trappings of sinister towers and dark deeds to the lighter voice of America's great humorous storyteller. But to those who know Sam Clemons beyond such crowd-pleasers as Tom Sawyer and Prince And the Pauper, it isn't such a big leap after all.With the exception of an early short story ("The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," neatly adapted by Kevin Atkinson), the bulk of the material in Mark Twain is lesser known fare. Instead of adapting The Adventures of Tom Sawyer or that giant of banned books, Huckleberry Finn, for instance, Pomplun scripts a 37-page adaptation of Twain's later attempt at cashing in on his beloved characters, Tom Sawyer Abroad. (The inclusion of Abroad in the new edition replaces several items from the first printing, including two pieces about P.T. Barnum's Cardiff Giant that this fan of humbug history would love to see.) General critical consensus has long placed Tom's travel adventure far below Finn or Sawyer in the pantheon of Twain's work, and it's true that the work's fantastic premise - Tom, Huck and loyal ex-slave Jim get trapped on a cross-oceanic balloon flight which carries them to the Middle East - is not in keeping with its more down-home Missouri-bound predecessors. But if the story's starting premise is a stretch, in many ways, Twain's sly take on American cultural imperialism proves even more applicable today than it was during its initial release. In the voice of Tom Sawyer, who typically presents American values in their most comically bald-faced fashion, our heroes fly to the Middle East "to recover the holy lands from the Payguns." "They own the land," Tom explains at one point, "but it was our folks, the Jews and Christians, that made it holy, and so they haven't any business to be there defiling it." Though spot on in its take on American self-importance, Abroad maintains a genial tone that's sustained by artist George Sellas' big-eyed cartooning. The later Twain works, best repped by "A Dog's Tale" and "The Mysterious Stranger," are considerably grimmer fare. In "Tale," adapted and illustrated by Lance Took, the writer focuses on human mistreatment of pets, a theme that's also briefly touched on in "Stranger." In Twain's eyes, nothing typified human depravity better than its arrogant abuse of "lesser creatures" – whether they be animals of human slaves – and Took expands upon this idea by presenting his adaptation as an illustrated theatre piece being dramatized by the "Uhuru-Kai (Free-Life) Family Theatre." If this approach occasionally blunts the impact of Twain's screed against animal experimentation, perhaps that's a good thing. Treated less emblematically, the story would be devastating. But for a more direct decent into the darkness of Twain's twilight years, there's Rick Geary's adaptation of Twain's unfinished novella, "The Mysterious Stranger." Set in the Middle Ages, it describes the visit of a blandly boyish figure named Satan ("He is my uncle," the mysterious stranger states at one point, though everything the character tells us is suspect), who gives two youngsters a series of lessons in human depravity and the uncaring nature of the cosmos. Ending with one of the most demoralizing declarations of disbelief that Twain ever penned, it's a lifetime away from the high-spirited tall-tale spinning of "The Celebrated Jumping Frog." Geary, the author of a striking series of graphic docu-novels devoted to Victorian Era murders, is definitely suited for this gloomy fare. You can really see him reveling in the material when Satan takes the lads on a tour of a prison torture chamber and a medieval sweat shop. Graphic Classics: Mark Twain concludes with "Stranger," so if you don't feel like finishing this book staring into the existential abyss, you might want to hold a few of the lighter pieces for last. Twain's "Advice for Little Girls" and "A Curious Pleasure Excursion" are more straightforward humor pieces that could've easily appeared in an issue of National Lampoon back in that mag's glory days. (Note the presence of NatLamp great Shary Flenniken as one of "Little Girls'" eight women illustrators.) And while "The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Conecticut" may be almost as cosmologically sardonic as "Stranger" (in it, Twain meets and murders his own conscience), British cartoonist Nick Miller's panels are so full of eyeball kicks that the whole piece reads as more goofy than despairing - even if the tale's final image is of our narrator standing over several buckets of severed Little Tramp body parts. Still, like I say, taken as a whole, Graphic Classics' Mark Twain set proves to be closer to the series' horror anthologies than you might initially think. As ol' Sam Clemens himself well knew, it doesn't take much to transform a chuckle into a shudder. Labels: classics illustrated # |Thursday, June 14, 2007 ( 6/14/2007 02:55:00 PM ) Bill S.  "AND NOW I SHALL NEVER BE ASHAMED OF LIKING UDOLPHO MYSELF!" – The cover to the most recent volume in the "Graphic Classics" series, Gothic Classics (Eureka Productions), depicts perhaps the most full-blooded moment in the collection: a scene from J. Sheridan Fanu's "Carmilla," showing the story's title vampiress lying in a leaden coffin filled with blood. Good stuff, indeed, for lovers of the outlandishly gothic, though unfortunately you'll search long through this 144-page collection to find another like it. "AND NOW I SHALL NEVER BE ASHAMED OF LIKING UDOLPHO MYSELF!" – The cover to the most recent volume in the "Graphic Classics" series, Gothic Classics (Eureka Productions), depicts perhaps the most full-blooded moment in the collection: a scene from J. Sheridan Fanu's "Carmilla," showing the story's title vampiress lying in a leaden coffin filled with blood. Good stuff, indeed, for lovers of the outlandishly gothic, though unfortunately you'll search long through this 144-page collection to find another like it.Edited by series mastermind Tom Pomplun, Gothic Classics contains adaptations of "Five Great Tales of Ghosts, Vampires, Haunted Castles & Forbidden Love!": "Carmilla," Ann Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho, Edgar Allan Poe's "The Oval Portrait," Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey, and M.J. Closser's "At the Gate." Of the five offerings, the most arguably successful are those that focus on shorter works: honing a beefy 18th–century novel like Udolpho or Northanger down to a 40-page comic mainly serves to heighten their haphazardness. In Rod Lott & Lisa K. Weber's retelling of the much-filmed horror tale "Carmilla," however, the focus remains on the story's bloody seductiveness (nicely captured by Weber's stylized penciling, which in places evokes a softer Richard Sala), while Pomplon & Malaysian artist Leong Wan Kok's four-page version of Poe's vignette smoothly catches the tone of this minor grim reflection on the obsessed artist. Of the three short pieces, only Pomplon & Shary Flenniken's "At the Gate" reads the most out of place as it isn't even a gothic short story. A sentimental tale of dogs in the afterlife, it really belongs in a different collection altogether (Animal Classics, perhaps), though it's an undeniable treat to see the "Trots And Bonnie" artist once more tackling expressive comic canines. Why isn't there a collection of this woman's underground and NatLamp work available? The two longer adaptations essentially play off each other: Austen's novel, adapted by Trina Robbins & Anne Timmons, was initially written as a parody of Udolpho, in fact – its primary joke (which wears thin long before the adaptation concludes, unfortunately) is to continually hint at impending perils which it never delivers. (David Chase is not the first writer to've pulled that particular trick!) While Robbins & Timmons both work mightily to recreate Austen's story, the source itself is such a filigreed trifle that after about twenty pages, you stop caring. Udolpho, for better or worse, is the template that centuries of romance writers have utilized to craft "ladies' gothics." It has everything you'd expect in a work of this type: a victim heroine thrown into the hands of villains by cruel fate, a crumbling castle with secret passages and a mysterious portrait, seemingly supernatural events that get "logically" explained (in this case, pirates are behind the seeming hauntings), poisonings, a wrongfully imprisoned dashing hero and more. If scripter Antonella Caputo is unavoidably text-heavy, Carlo Vergara's detailed art beautifully captures each teardrop and shadowy corridor. And while its plot isn't a model of air-tight construction, Udolpho's underlying theme – of women imperiled by an avaricious patriarchal culture – still holds it all together. In one of Northanger's better moments, novel-addled heroine Catharine Morland is shocked to learn that a handsome young gentleman is also fan of Udolpho: "You never read novels, I dare say," she states before learning the truth. "Gentlemen read better books." Despite its frequent status as second-class literature, gothic literature has endured, in part due to its transgressive disrespect for the niceties of realistic plotting. While Gothic Classics only occasionally touches on the genre's more sensationalist tendencies (you wanna do a truly gothic piece, why not adapt Castle of Otranto or, better yet, The Monk?), the sight of a willowy young girl holding onto a flickering lantern as she tremulously treads toward who-knows-what (check out Trina Robbins' back cover illo for a super-fine example of this image) is still rife with "forbidden" connotation . . . Labels: classics illustrated # | |

|

|

Pomplun’s adaptation of Jekyll and Hyde takes an approach that might alienate hard-core comics purists: dividing the two-part story and treating the first at as a straight Simon Gane illustrated comic with the second as a piece of illustrated prose accompanied by a single Michael Slack illo per page. As Stevenson’s original was written from two distinct perspectives -- the first that of Henry Jekyll’s straight-laced friend Utterson, the second from the journal confession of Jekyll himself -- the shift in style doesn’t prove all that jarring, though I have to admit preferring Gane’s heavy ink work over Slack’s lighter graphics. It suits Stevenson’s horror tale better.

Pomplun’s adaptation of Jekyll and Hyde takes an approach that might alienate hard-core comics purists: dividing the two-part story and treating the first at as a straight Simon Gane illustrated comic with the second as a piece of illustrated prose accompanied by a single Michael Slack illo per page. As Stevenson’s original was written from two distinct perspectives -- the first that of Henry Jekyll’s straight-laced friend Utterson, the second from the journal confession of Jekyll himself -- the shift in style doesn’t prove all that jarring, though I have to admit preferring Gane’s heavy ink work over Slack’s lighter graphics. It suits Stevenson’s horror tale better.